Mid way through Dyslexia Awareness Week and I thought I would share our dyslexia story with you. Talking to parents at a local dyslexia meeting earlier this week, I was again struck with the sheer frustration we deal with on a daily basis. The importance of being your child’s biggest and best advocate has never been more essential. The pressure placed on our children by the ‘perfect’ worlds portrayed through social media are multiplied if they are feeling crushed by their differences. Mental Health Awareness Day highlights the need for us to be there for our children, to listen to their thoughts and feelings and to take them seriously. This is our dyslexia

story….

Our daughter was first diagnosed with a hearing problem by her nursery. She refused to sit down for story time, preferring to cartwheel instead. “She’s not a naughty girl, so I wonder if it might be her hearing?”, questioned her teacher. Deaf in one ear was the conclusion of her hearing specialist. The immediate response from the nursery was that she should be sat close to the teacher who should look directly at her when talking and slow down their speech. This had a profoundly positive effect on her behaviour.

What did not change, however, was her inability to read or grasp new sounds and phonics. At the time we had no concept of SEN. Our older son was an avid reader and was flying high academically. Even though my husband is dyslexic, he has always viewed it as ‘his normal’. We didn’t want a problem and, so, we were happy for the “experts” to convince us that there was not a problem with our little girl.

Gradually, realisation began to dawn. Reception and Year 1 at school became a battle with teachers. Zero progress on reading, struggling to do up her shoe laces and using her own “signs” for some words should have been big red flags, but they were not; her teachers constantly told us not to worry as “they all develop at a different pace”.

Two weeks into Year 2, we received a message from her new teacher: “I think we may have a problem”. Some parents might respond to that message with a sinking heart but for us, it was the opposite. At long last someone recognised what we had suspected for three years. Finally, issues were being addressed and, once the possibility that my daughter had dyslexia was considered, additional help from the school was given immediately.

From Year 2 onwards, she had one-to-one tuition in English and maths as well as help from a teaching assistant (TA) in her classes. She hated being taken out of class for her “special lessons”, as she called them (and not in a positive way). The saving grace came from Year 3 onwards when there were sports matches every week; she was the star of every “A” team. It really makes me question the self-confidence of pupils with SEN who do not identify an area in which they can shine.The importance of finding their ‘thing’ is just so essential and then giving them the time to make the most of their talents. We fought for her to miss lessons in order to go to county netball training sessions because netball gave her so much more in self-confidence than a late afternoon RS lesson.

As she progressed through school, I was forever frustrated that she was given the same text books as her fluent-reading peers. What was the point? She refused to even open them and, as a result, fell further behind. Her defence mechanism was simply not to try. If you don’t put yourself out there, you cannot fail, can you?

Extra help

Every year we had to make sure that we personally made all her teachers aware of her issues. Initially, I had assumed that this information would be passed on but it wasn’t. I requested that she was not asked to read out loud in class; however, that didn’t go down well with some teachers. Somehow I doubt if anyone would ask a child with one leg to run in front of the rest of the class but, for some reason, it is fine to ask a child who can’t read to read out loud. Learning songs for the choir and lines for school plays was also tricky. Teachers just needed to give me the information well ahead of time and we could prepare for it, but they rarely did, which made the stress of those moments immense and heart-wrenching.

In Year 7, we decided to push for her to get extra time, a reader and a scribe (if she needed it) for her exams. The visit to the educational psychologist was mind-blowing. I truly thought she would be telling me that she was mildly dyslexic. Instead, I was told that she was severely dyslexic, had an incredibly slow processing speed and that she was amazed my daughter was managing to function in mainstream school at all.

At this point, her school began to question whether she should stay there. Being in the private school sector, she also faced the prospect of sitting Common Entrance exams at 13 to get into her senior school. These exams are tough for any pupil and the general consensus was that she did not stand a chance. But she was so far down the line and happy with her peers, that a change would not have helped her sport.

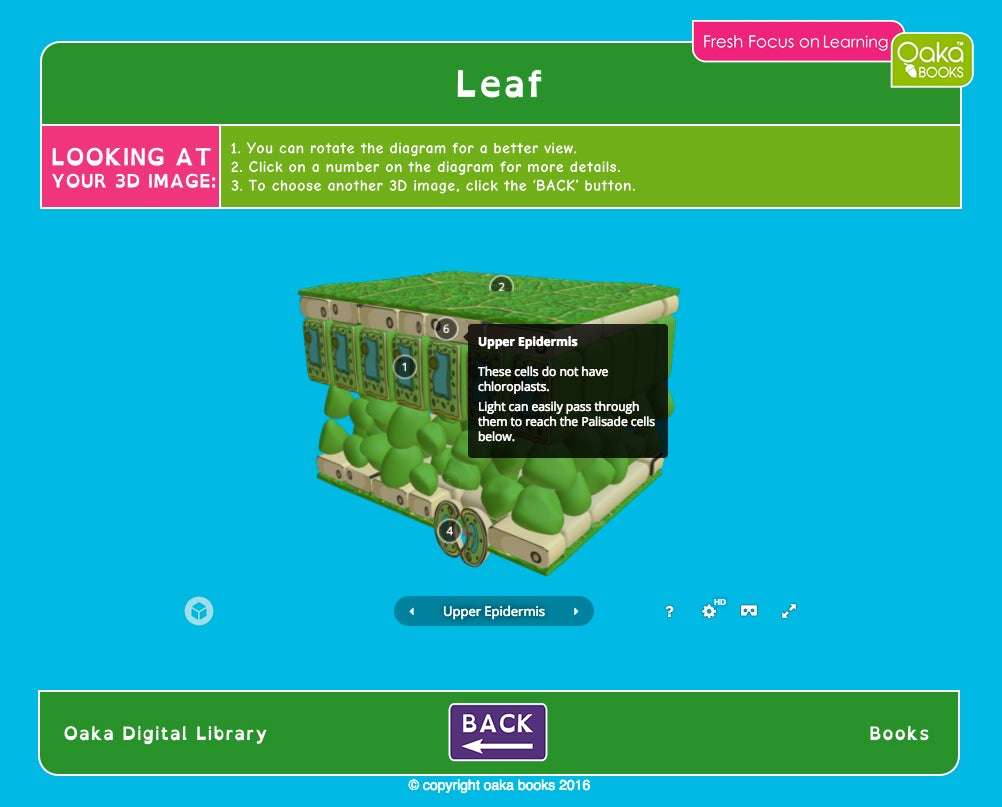

By now, the learning support (LS) department in the school was offering all sorts of interventions, most of which she refused to participate in. She simply did not want to be different. We had to create our own resources at home to suit her learning style and eventually, this developed into Oaka Books.

Working it out

For many children with SEN, being labelled can provide relief – knowing there is a reason they find certain things tricky. They may also begin to understand why they see the world in a different way and the benefits this may bring. Our daughter’s reaction to being diagnosed as dyslexic with a slow processing speed was: “So, I’m not actually stupid?” It was then a case of understanding how best to work with her learning differences and come up with alternative ways for her to access information. Creating our own resources to make her learning very visual and kinaesthetic worked wonders for her.

If you put a penguin and a hawk together and try to get them to fly, the penguin will still be sitting on the ground, no matter how hard it flaps its wings, long after the hawk has soared away. Sometimes, desire and effort just won’t overcome physical or mental limitations. So, we work within her limits and always aim for her to be the best that she can be.

She was showing her prowess on the netball court and was selected as a county player. Something that became very evident was that she was able to totally read a game, be in the right place at the right time and make quick decisions. On the other hand, I remember watching a girl who was very academic constantly throwing the ball to the opposition. That made me realise that we just needed to put our square peg into a square hole and not try to fit her into a round one.

Making progress

She went on to a college where they have a superb LS department. However, even with their amazing support, she struggled through her GCSEs. One-to-one sessions worked brilliantly, as she did not have the classroom pressure and felt safe and comfortable to ask questions. We began revising for her exams before Christmas so she had enough time to cover every topic.

The final term before her GCSEs was tricky; she found revision hard and so the school supported our decision to keep her at home. For the first time, she really took control of her learning. I will never forget her face when she opened her exam results to see AABBBC.

I am so proud of her achievements. She was the student who progressed most in her year from mocks to exams. She played netball at Regional Performance Academy level, gained a Double Distinction in her BTEC in Sports Science and is now studying Sports Performance at Bath University.

So, what have we learned? As parents, we need to make ourselves aware of our child’s issues early on, not sweep them under the carpet. We need to (sometimes) challenge what we are being told by the “experts”. We need to arm ourselves with knowledge and understanding of what options are available and what help we can get for our child as early as possible. We need to understand and embrace the facts that all children are different. We need to be prepared to be their lion or lioness.

Hawks may be great at flying but they don’t swim, and our penguin is swimming brilliantly.